Forced labor risk assessment

A comprehensive model for organizations to assess risk exposure to forced labor and extreme labor exploitation

Assessing forced labor risk in an organization and its supply chain is complex. This paper provides an overview of Moody's Forced labor risk solution, which helps companies uncover forced labor risk more efficiently and effectively. It enables companies to conduct deeper investigative research as part of their enhanced due diligence. The model quantifies forced labor risk across business, industry, and country-specific components, facilitating cost-effective due diligence. The research and logic behind the structure of the model are detailed, along with methods used to select, build, and standardize metric datasets, inform model algorithms, and validate outputs. The complementary product risk flag analysis is described, providing alerts of forced labor incidents in product supply chains. Transformation techniques then allow model outcomes to be presented as risk categories and recommended actions to be extracted from an insights database. The resulting model output provides organizations with a detailed risk assessment, expert interpretation of risk, and guidance on taking meaningful action.

Scope and terminology

This solution measures the risk of severe forms of labor exploitation, including forced labor, modern slavery, and human trafficking, and the degree to which an organization may have a severe lack of resilience and capability to respond to these exploitation risks. The solution uses the terminology of forced labor and labor exploitation to indicate its focus on forms of exploitation that can taint the supply chains and operations of businesses, for example, forced labor in agriculture, fishing, manufacturing, mining, construction, and the service sector. This includes forced labor in the private economy and state-imposed forced labor. In countries with modern slavery legislation, including the UK and Australia, the solution can be understood as a modern slavery risk assessment solution, as it was built to measure the risk of modern slavery forms that enter business operations and supply chains (forced labor and trafficking for labor exploitation, rather than, for example, forced marriage and trafficking for sexual exploitation). In countries where national and business action plans use the language of trafficking in persons, the solution can be understood as a human trafficking risk assessment solution, as it was built to measure the risk of trafficking for labor exploitation (rather than, for example, trafficking for sexual exploitation or forced surrogacy). See further details on terminology in the appendix.

Introduction

The Forced labor risk assessment is a risk assessment solution for forced labor. Created by the Rights Lab, the world’s leading and largest modern slavery research group, it uses Rights Lab proprietary data, other high-quality datasets, and organization-specific information to calculate forced labor risk. The solution combines and weights a wide range of global datasets as indicators of the level of forced labor risk across business, industry, and country categories. This risk is cross-checked against key datasets that provide partial indicators of slavery’s presence (case/incidence data) in countries and sectors. The Forced labor risk assessment generates scores, provides recommendations, and flags product-related instances of forced labor. The solution operates across worksites, sectors, geographies, products, suppliers, and investments. Where citations for individual data sources are required, identifiers are given within the document or in the metrics tables in square brackets [], referring to the citations section at the end of this document.

Model structure

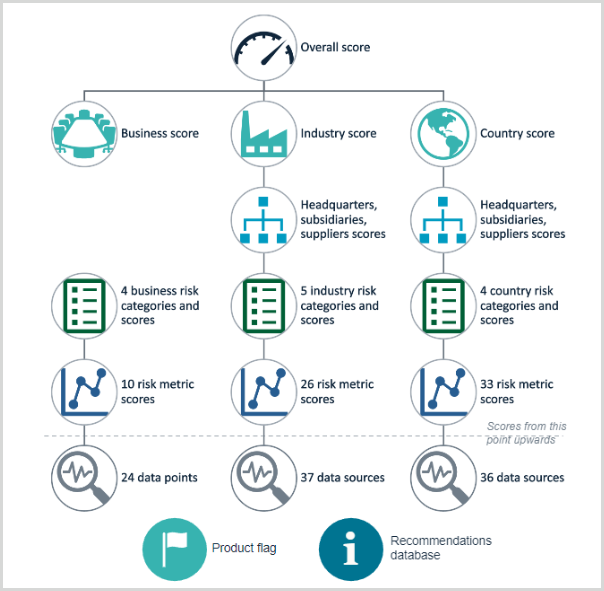

Risk is scored at the level of individual metrics and as combined weighted totals for risk management categories and then organizational components to give an overall organizational score. The total number of risk scores available across the whole model is circa 2000, representing the most comprehensive risk analysis available for forced labor. See Figure 1 for an overview of the model structure.

Figure 1: Model structure

The overall risk score for an organization is the weighted total of three risk component scores: business, industry, and country.

Business metrics are scored based on a range of financial characteristics of the organization, and an assessment of employee and supplier behaviors. The overall business score is a weighted sum of 10 individual metric scores.

The industry and country risk scores are weighted totals of three further risk sub-components: headquarters (HQ), suppliers, and subsidiaries (omitted if not applicable).

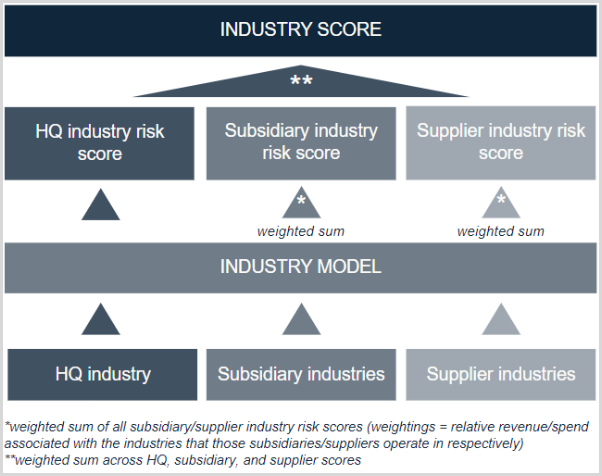

The industry scores relate to an organization through its main industry/sector and the main industries associated with its primary (tier 1) suppliers and subsidiaries. Similarly, the country scores relate to an organization through the locations of the organization’s HQ and the locations of its primary (tier 1) suppliers and subsidiaries – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: How industry scores are calculated (also applies to country scores)

Given an industry/sector, a risk score is looked up from the Rights Lab industry risk model – described in section 3. An HQ industry score is the looked-up risk score for the main industry/sector in which the organization operates. An overall subsidiary industry score is the weighted sum of all subsidiary industry risk scores for the organization, where weightings are based on the relative revenue associated with the industries in which the subsidiaries operate. An overall supplier industry score is the weighted sum of all supplier industry risk scores for the organization, where weightings are based on the relative spending associated with the industries in which those suppliers operate. Furthermore, the individual industry scores - the HQ score and each of the subsidiary and supplier scores - are themselves a weighted sum of 26 individual metric scores.

Given a location, a risk score for that country is looked up from the Rights Lab country risk model - described in section 4. An HQ country score is the looked-up risk score for the HQ location. An overall subsidiary country score is the weighted sum of all subsidiary country risk scores for the organization, where weightings are based on the relative revenue associated with the subsidiary locations. An overall supplier country score is the weighted sum of all supplier country risk scores for the organization, where weightings are based on the relative spend in those supplier locations. Furthermore, the individual country scores - the HQ score and each of the subsidiary and supplier scores - are themselves a weighted sum of 33 individual metric scores.

All scores are based on user input data. Missing data is penalized by assigning the corresponding metric the highest risk score.

Within the Forced labor risk assessment model, all metrics have been created from normalized datasets – this means that their risk scores are on an equivalent risk scale for ease of comparison.

Model component design

The industry and country components were developed through a sustainable development lens. Forced labor hinders development by fostering corruption, institutionalizing inequality, and reinforcing intergenerational poverty. The impacts of forced labor on economic and human development have implications for business risk and response, including slavery’s damage to productivity, multiplier effects, and innovation in production, and its relationship to illicit financial flows and environmental harm.

Further details on the construction of the three main components of the Forced labor risk assessment model - business, country, and industry - are provided in this paper. Within each component, the metrics are broken down into several sub-groupings. These have been mapped to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) categorizations for country and industry metrics using new research and use a Rights Lab categorization for the business metrics. Details of the selected metrics and their relationship to forced labor are given.

Model weightings

Having established the business, industry, and country components of the Forced labor risk assessment, a Delphi approach was employed to assess the relative significance of those three components and the three sub-components that sit beneath country and industry: HQ, suppliers, and subsidiaries. Within this method is a forecasting process framework based on the results of several iterative rounds of questionnaires sent to a panel of experts, in this case Rights Lab subject matter experts, selected for a balance of disciplinary expertise and approaches. The weightings assigned were then optimized via designed experiments using sample company datasets and simulation.

When scores are presented within the respective business, country, or industry sub-groupings (in this paper and in the Forced labor risk assessment itself), each sub-group is presented in order of its weighting - that is, according to its relative contribution to its respective component of the Forced labor risk assessment. Similarly, each metric within each sub-grouping is presented in order of its relative contribution to the sub-group.

Model validation

The prevalence of forced labor is difficult to estimate, whether at a national level or at the level of industry and sectors, not least because it is often actively hidden by organized criminals. Nevertheless, some existing datasets reveal potential trends that can be compared against our risk scores for countries and industries. For the country risk model, several datasets were compared, including the Rights Lab's Contemporary slavery in armed conflict dataset and the Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) database. For the industry risk model, the Rights Lab undertook an original piece of research to combine data from multiple sources to generate a database of industry-level instances of forced labor, including data from the ILO, UNOC, US Department of State, and US Department of Labor.

Risk score and data evolution

Country and industry scores may remain relatively consistent year-on-year, aside from locations with emerging conflicts or natural disasters - assuming an organization’s supplier and subsidiary countries/industries remain consistent. By contrast, the business component functions as a ‘residual risk’ score, where an organization with strong social sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) approaches can reduce its overall risk score, independent of the risk associated with location and industry components.

The Forced labor risk assessment model has been built to allow data updates without changes to the underlying method. The consistent SDG framework means that more datasets can be added as the Rights Lab completes new research or as data is refreshed at regular intervals. Users can have confidence that changes to risk scores are not due to the method changing but rather changes in risk, enabling them to chart progress and compare results over time.

Business risk model component

The 10 business metrics are grouped into four categories, shown in the tables below. These metrics were developed through extensive original research and literature review. They generate an overall business risk score that combines sub-scores across multiple categories of business practice and culture - including worker rights, governance, resilience, and transparency - which map to the internal issues that most influence forced labor risk for an organization. The relative significance of each of the 10 metrics was established through a Delphi approach, engaging a panel of Rights Lab business researchers in a weightings estimation, individually at first, followed by an iterative refinement of the weightings until a consensus was achieved across the panel.

Business sub-categories

Worker relations, rights, and remedy

This category of metrics measures the quality of worker relations, rights, and remedy. Forced labor takes root in work environments with low respect for individuals and their rights to decent work, high turnover rates, and low labor costs.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Worker voice and labor rights | The level of commitment to a range of labor rights and worker voice, established by surveys. It includes the ability of workers to join unions and participate in collective bargaining, provide feedback to management or owners, raise concerns or grievances, request improvement to conditions, and receive fair remedy when there have been worker rights issues. Labor exploitation thrives more easily in environments that do not protect worker rights and enable worker voice. |

Labor cost resilience | The labor cost resilience, calculated using the average labor cost per employee. A low labor cost per employee correlates with low-skilled, labor-intensive activities, in which workers are more vulnerable to severe labor exploitation and forced labor because they have few or no alternative ways to make a living. |

Workforce turnover | The workforce turnover, calculated using the voluntary plus involuntary employee turnover percentage. There are strong links between a high workforce turnover and poor working conditions, including repetitive tasks, lack of autonomy, and precarious contractual arrangements. High turnover can also increase the workload for remaining employees. |

Governance and commitments

This category of metrics measures the extent of human rights corporate governance. Where organizations have poor governance and lack ethical frameworks, the risks of forced labor become higher.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Human rights policies and management | The extent of human rights policies, practices, and governance established via survey. Forced labor is more difficult to identify and mitigate against in contexts without specific human rights policies. Human rights policies help to drive practices like human rights risk assessments and remediation. |

Remuneration inequality | The renumeration inequality, calculated using the ratio of CEO pay to median employee pay. A high CEO-to-median employee pay ratio can indicate organizational inequalities, a culture that does not promote fair pay, or where workers lack negotiating power. |

Organizational resilience

This category of metrics measures the extent of organizational resilience. Where cost pressures are high and knowledge intensity is low, organizations have less capacity to reinvest in workers and working conditions.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Knowledge intensity | Knowledge intensity, calculated using the average spend on research and development per employee. Organizations with high levels of research and development investment per employee tend to attract highly skilled workers. These organizations pay higher wages, generating higher-value products or services, margins, and a competitive advantage through innovation, reducing the risk of labor exploitation. |

Balance sheet pressure | Balance sheet pressure, calculated using the ratio of debt to equity. Organizations with highly leveraged, weak balance sheets are more likely to prioritize short-term operational performance over longer-term commitments to ethical governance. Poor financial health creates an environment that can impact working conditions and raise the risk of exploitation. |

Cost resilience | Cost resilience, calculated using the average sales per employee. An organization in which employees generate a high level of income or revenue would result in less pressure on the costs of employees and the associated risk of labor exploitation. |

Supplier management

This category of metrics measures the quality of supplier sourcing and management processes. Forced labor can more easily take root within organizations that have poor visibility and control of their supply chains.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Procurement and contract management | The quality of approaches to sourcing and managing the supplier base established by survey. A robust policy for responsible sourcing and awarding contracts increases supply chain transparency and the ability to mitigate against forced labor risks when used with an ethical approach to supplier management. |

Supply chain concentration | The concentration of a supply chain, calculated using the average sales per supplier. As the level of sales per supplier decreases, the complexity of the supply chain increases, making it more challenging to audit and monitor for labor risks. Forced labor is better concealed in complex supply chains. |

Industry risk model component

The Rights Lab’s industry risk model spans 21 industry NACE categories. NACE is a standard categorization that encompasses all economic activities. The industry-based scoring system uses 37 industry-focused datasets to represent 26 metrics; some of these are simple datasets and others are composite. At an overarching level, the metrics were developed through a sustainable development lens. However, as the UN’s targets are inherently focused on the national level, the relationship to industries/sectors is less straightforward. Individual metrics were identified through an extensive program of original research into the issues that most influence forced labor risk within industry. At the same time, an alignment to SDG goals was retained as a guiding framework. To this end, the 26 metrics are grouped under five SDG categories, as shown in the tables below.

It should be recognized that while the reporting of country-level data is common, datasets that span all or at least some industry sectors are much less common. Furthermore, even when such data is available, the reporting of data within defined industry sectors, such as the NACE classifiers, is somewhat exceptional. Therefore, one significant component of Rights Lab research was the mapping of datasets from their original sectoral breakdown into NACE-based industry breakdowns.

Each of the 21 industry risk scores is a weighted sum over 26 individual scores derived from the metrics - the more metrics within an industry that are high risk, the more likely that the environment enables forced labor to exist and thrive. The relative significance of each of the 26 metrics was determined using a two-stage weighting process: one at a higher level of the five SDGs, and a second at the more granular level of the individual metrics. In this way, the levels of significance of the five SDGs to forced labor within industry were able to be separately assessed, as well as the significance of each of the metrics that sit within those five individual SDGs. The weightings were determined by a combination of literature reviews and a Delphi approach, using a panel of Rights Lab experts to estimate the weights. This involved individual assessments at first, followed by a refinement of those weightings - iteratively engaging with the individuals until the panel reached a consensus.

Industry sub-categories

SDG 8 - Decent work - Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all

This category of metrics measures the extent to which decent work is available. Forced labor takes root in industries that do not protect labor rights and promote safe working environments, and where child labor levels are high and wages are low.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Migrant worker rights [30] | The extent to which migrant workers are deprived of work-related rights, such as being unable to change employers or communicate with people outside job sites, within industry. Migrant workers are more likely to be deprived of work-related rights than non-migrant workers, as in many countries they cannot legally join a union. Migrant workers are more likely to have informal working arrangements and insecure contracts, making them more vulnerable to exploitation. |

The level of child labor within industry. There are strong correlations between child labor and forced labor. Both forms of exploitation thrive where there are high levels of informality in an industry, which creates challenges for government inspection and business due diligence measures. In addition, the "worst forms of child labor," as defined by the International Labour Organization, include slavery, child trafficking, and forced labor. | |

Human rights policies on forced labor [40] | The extent to which forced labor is addressed in human rights policies within industry. Forced labor can more easily take root in contexts without specific policies to address these risks within human rights commitments. These policies help to drive practices like human rights risk assessments and remediation processes. |

Labor policies on forced labor [40] | The extent to which forced labor is addressed in labor rights policies within industry. Forced labor can more easily take root in contexts without specific policies not to use or benefit from forced labor. These policies help to drive practices like labor rights risk assessments and living wage commitments. |

Wage levels [41] | Average wages within industry. Sectors characterized by low-paid labor have higher levels of forced labor. Workers earning wages at or below the poverty line are more vulnerable to severe labor exploitation and forced labor because they have few or no alternative ways to make a living. |

Hazardous conditions (fatal) [41] | The level of fatal occupational injuries within industry. Forced labor victims are likely to endure working conditions that workers would not freely accept, including conditions that are hazardous and cause death. For example, they may work in dangerous environments that expose them to tunnel collapses, heavy loads, explosions, and chemical substances. |

Hazardous conditions (non-fatal) [41] | The level of non-fatal occupational injuries within industry. Forced labor victims are likely to endure working conditions that workers would not freely accept, including conditions that are hazardous and cause serious illness or injury. For example, they may lack adequate protective gear, use dangerous equipment, or work long hours in extreme heat. |

SDG 13 - Climate risk - Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

This category of metrics measures the extent of climate change-related impacts. Climate change, environmental degradation, and forced labor are highly interconnected. Climate change increases vulnerability to forced labor, and industries with high levels of forced labor destroy the environment. There is a positive relationship between stronger environmental protections and lower estimated cases of forced labor.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Air pollutants [42] | The level of air pollution within industry. Polluting activities are often highly reliant on intense, manual labor in which workers are subjected to forms of exploitation that are supposedly cheaper than upgrading to new technologies. Often, the same remoteness and isolation that protects a work site from environmental monitoring and enforcement will also prevent labor inspections. In addition, air pollution also leads to poor health, potentially reducing access to livelihoods, and increases migration, raising risks of trafficking during unsafe migration journeys. |

Carbon emissions [43] | The share of global greenhouse gas emissions within industry. Enslaved labor is routinely utilized by some of the most ecologically toxic industries on earth, like brick making, clear-cut deforestation, precious-woods logging, and strip mining. Criminal slaveholders who do not adhere to environmental laws and treaties are a leading cause of the natural world’s destruction, and modern slavery, including forced labor, is one of the world’s largest greenhouse gas producers. |

Tree loss [26] | The extent of tree cover loss within industry. There is a strong correlation between forced labor and tree cover loss in multiple countries, especially within illegal deforestation and land clearing. This is a two-way relationship. When biological diversity decreases due to tree cover loss, vulnerability to slavery increases. In turn, this increases forced labor's contributions to tree cover and biodiversity loss. An estimated 40% of deforestation is accomplished with workers subjected to forced labor. |

Water footprint [44] | The amount of water used within industry. Industries with large water footprints are those that use a large volume of freshwater to produce goods and services. A large water footprint may mean water stress and, therefore, increased poverty and vulnerability for local communities that depend on freshwater supply for their livelihoods. Lack of potable water is an indicator of indecent living conditions and is an indirect push factor into forced labor. |

Water pollutants [42] | The level of water pollution within industry. Illicit operations are more likely to subject workers to forced labor and also to hide their environmental crimes, including the dumping of hazardous wastes into water sources. There are increased levels of risk for women of human trafficking as they walk further to obtain clean water. |

SDG 5 - Gender equality - Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

This category of metrics measures the extent of gender inequality. Women are disproportionately vulnerable to forms of modern slavery due to gender discrimination and lack of equal opportunities. Forced labor takes root in industries where gender inequalities also combine with other drivers of vulnerability that disproportionately impact women and girls: migrant worker recruitment costs, informal employment, and lack of access to education.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Migrant worker recruitment costs [30] | The level of recruitment fees paid by migrant workers within industry. A major cause of forced labor in global supply chains is the charging of recruitment fees to migrant workers. To pay large fees to recruitment agents, migrants often take out high-interest loans. This debt burden exacerbates their vulnerability and can lead to debt bondage and forced labor. The practice of charging migrant workers for recruitment is prohibited in many countries yet remains common. Women migrants tend to pay more than men, may feel more dependent on the recruitment agent for protection, making them more vulnerable to abuse, and may have had less control during negotiations over work contracts where these were negotiated by male relatives. |

Informal employment [41] | The level of informal employment rate within industry. Where economic activity is beyond government regulation and protection, there are few legal mechanisms protecting rights to decent work. Workers in the informal economy are unlikely to have contracts and access to social protections. They are more likely to experience unsafe work conditions, forced overtime, low wages, precarious employment, and labor exploitation and abuse. In most countries, women make up a higher percentage of the informal economy. |

Gender equality policies [40] | The extent to which gender equality is addressed in human rights policies within industry. Modern slavery, including forced labor, can more easily take root in contexts without specific policies on gender equality in human rights commitments. These policies help to drive practices like anti-harassment action and gender-sensitive health and safety measures. |

Education levels [41] | The level of education within industry. Poor access to education increases vulnerability to forced labor, and experiencing forced labor is linked to poor educational outcomes. Individuals with lower levels of formal education have fewer formal and skilled employment prospects and are more at risk of exploitation. In many countries, girls are less likely to receive quality education and more likely to drop out of school. This makes them more vulnerable to trafficking, including as women migrants seeking low-skilled work abroad. |

Gender pay gap [41] | The gap between male and female pay within industry. The discrimination that drives a pay gap also drives the exploitation of women workers. Unequal economic access can impact a woman’s level of control over their job and make them less able to mitigate emergency situations and economic shocks, creating vulnerability to exploitation. |

SDG 9 - Industry, innovation, and infrastructure - Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation

This category of metrics measures the extent of industrial resilience, inclusivity, and sustainability. Forced labor takes root more easily in industries structured around a temporary or low-skilled workforce, with lower levels of investment in innovation and improvement, and with less regulation from trade governance instruments.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Temporary and seasonal workforce [45] | The share of the workforce with involuntary temporary contracts within industry. There is widespread documentation in many countries of disproportionate exploitation within temporary and seasonal work. The lack of regulations and protections for migrant, temporary, and seasonal workers' rights often results in low wages, poor working conditions, and employee abuse. Precariously employed workers often lack access to trade unions and employer associations. |

Foreign migrant workers [41] | The level of foreign migrant workers within industry. Migrant workers are more likely to be exploited through forced labor than non-migrant workers due to insecure immigration status, lack of access to public services, and language barriers. They are less likely to raise grievances with their employers or the authorities. Immigration systems based on work sponsorship can create dependencies on employer sponsors, potentially placing migrant workers in situations of coercive control. |

Workforce skills level [46] | The level of skill in the workforce within industry. Low-skilled workers, including migrant workers, are prone to abuse by recruitment agencies and employers. Employers of higher-skilled migrant workers normally cover recruitment costs, whereas lower-skilled migrant workers often pay agencies high fees. Low-skill positions are more likely to be characterized by flexibility, insecurity, precarious employment, and long working hours with low pay. The informal economy, where workers are not protected under labor legislation, is characterized by low levels of skill. |

Levels of purely domestic output [47] | The proportion of total output that is for purely domestic use within industry. Sectors that are less exposed to global value chains, with more value-add being consumed domestically, are more isolated from international leverage. Increasingly, there is international pressure and scrutiny in the areas of human rights standards, forced labor, and decent work. |

R&D intensity [48] | The intensity of research and development expenditure within industry. Sectors with low research and development intensity tend to pay lower wages, not attract highly skilled workers, and not focus on generating higher-value products or services, margins, and competitive advantage through innovation. These factors create a higher-risk environment for labor exploitation to take root. |

SDG 12 - Sustainable production and consumption - Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

This category of metrics measures levels of labor sustainability. Where industries have low labor costs, practices of excessive overtime, little regulation, and high price pressure, they are more likely to create environments in which labor exploitation can thrive and forced labor risk is heightened.

Metric | Description |

|---|---|

Labor productivity [49] | The level of labor productivity within industry. Sectors with low gross value added per hour worked are more likely to seek to reduce labor costs through illegal wage deductions, lack of overtime pay, wages below the legal minimum, or non-provision of benefits, which create a higher-risk environment for exploitation. |

Low labor cost [41] | The average labor cost per employee within industry. Industries with a low labor cost per employee are more likely to have low-skilled, labor-intensive work. Workers may lack other employment opportunities, giving them less power to negotiate for decent work conditions. Low labor costs often go hand in hand with insecure employment practices, further raising the level of vulnerability to exploitation. |

Levels of regulation [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] | The level of regulation within industry. Forced labor occurs most frequently in unregulated, underregulated, or hard-to-regulate sectors. Work that occurs outside of appropriate regulatory protection is more likely to have deceptive recruitment, degrading conditions, limited access to social protection, health and safety violations, abuse of worker vulnerability, or coercive practices. |

Excessive overtime [41] | The level of excessive overtime within industry. Frequent use of excessive overtime is one of the most common forced labor indicators. Compulsory overtime above the legal limits can constitute forced labor when combined with the threat of a penalty. Excessive overtime indicates worker vulnerability or coercive practices, both of which raise the risk of forced labor. |

Country risk model component

The Rights Lab’s country-based scoring system uses 36 global datasets within 33 key location-based metrics, to generate country risk scores.

The Rights Lab first defined a list of 200 nation-states and territories. This list was a combination of UN member states, additional states and territories from the World Trade Organization (WTO) member list that were not featured in the UN member states list, and countries identified as common locations for subsidiaries. The rationale was to create a comprehensive list that would be as relevant to business and trade as possible; further countries can continue to be added as deemed relevant.

The 36 global datasets were selected from a long list of 150, in a process of extensive original research. They include Earth Observation (EO) data. The datasets were mapped to 33 metrics, which are drawn from the 33 individual UN SDG target issues that most influence forced labor risk for countries. The 33 metrics are in four main SDG categories, as shown in the tables below.

The relative significance of each of the 33 metrics was determined through the deployment of a comparative judgment survey to a large proportion of Rights Lab team members to provide collective input. This is a well-evidenced approach for harnessing collective knowledge and, in appropriate circumstances, has been shown to be subject to fewer biases and inconsistencies than alternative techniques.

Country risk scores have been generated for the 200 countries, with each score a weighted sum of the 33 metrics - the more high-risk metric scores within a location, the more likely the environment enables forced labor to exist and thrive.

Country sub-categories

SDG 16 - Peace, justice, and strong institutions - Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels

This category of metrics measures the level of peace, justice, and strong institutions. Forced labor systems thrive in contexts without effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels. Forced labor is prevalent where there is conflict or a weak rule of law.

Metric | SDG target | Description |

|---|---|---|

Violence and torture | 16.2 End abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children | The level of violence within countries. Modern slavery, including forced labor, takes root in contexts with high levels of sexual and criminal violence and high levels of torture and extrajudicial killings. |

Public sector corruption [1] | 16.5 Substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms | The level of public sector corruption within countries. Forced labor is closely linked to illegal activity and corruption. Traffickers corrupt public officials and pay bribes. High levels of corruption among public officials correlate with failures in the overall implementation of anti-slavery policies. |

Anti-slavery legislation | 16.3 Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all | The extent of countries' domestic legislation against human exploitation. Countries without strong laws prohibiting slavery, servitude, forced labor, and human trafficking cannot effectively prevent people from enslaving others or provide sanctions in the instance of violations. |

Organized crime [2] | 16.4 By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets, and combat all forms of organized crime | The level of organized crime within countries. Human trafficking is currently the most pervasive global illicit market, now surpassing the illegal cannabis trade and arms trafficking markets, and there are strong links between human trafficking and other forms of organized crime, including drug trafficking, cybercrime, and money laundering. |

Internally displaced persons [3] | 16.a Strengthen relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for building capacity at all levels, in particular in developing countries, to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime | The level of internally displaced persons within countries. Where people flee due to armed conflict, generalized violence, violations of human rights, or natural or human-made disasters, and governments lack the capacity to provide protection and assistance, there is greater vulnerability to labor exploitation. |

Birth registration levels [4] | 16.9 By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration | The level of birth registration within countries. Without legal proof of identity, children are uncounted and invisible. Birth registration helps to protect children from exploitation. When children are unable to prove their age, they are at higher risk of being forced into the labor market. Migrant and refugee children with legal proof of identity are better protected against trafficking, illegal adoption, and family separation. |

Armed conflict [5] | 16.1 Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere | The level of armed conflict within countries. Modern slavery and human trafficking are present in 90% of modern wars. This exploitation includes forced labor by one or more sides in a conflict in industries that generate income for the armed group, or forced labor by other groups taking advantage of weakened rule of law in conflict contexts. In both instances, this forced labor enters global supply chains. |

Political violence and terror [6] | 16.7 Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels | The level of political violence and terror within countries. Modern slavery, including forced labor, takes root in contexts with low levels of inclusive, participatory governance and high levels of state-sanctioned killings, torture, disappearances, and political imprisonment. |

Government anti-slavery efforts [7] | 16.6 Develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions at all levels | Government performance on tackling modern slavery, including forced labor, within countries. Forced labor thrives in contexts where a government does not make sustained efforts across forced labor prevention, protection, and prosecution, including in the areas of survivor support, procurement of goods and services, and addressing key risk factors. |

Freedoms of movement, speech, and religion | 16.10 Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements | The extent of government respect for fundamental freedoms within countries. Vulnerability to modern slavery, including forced labor, increases in contexts with low levels of respect for human rights to freedom of movement, speech, assembly, association, and religion. |

Institutional discrimination [8] | 16.b Promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development | The level of institutional discrimination within countries. Formal and informal laws, social norms, and customary practices that increase gender inequalities and limit women's social and economic participation create contexts of vulnerability for women and girls to early marriage, human trafficking, and forced labor. |

SDG 8 - Decent work - Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all

This category of metrics measures the degree to which decent work is available. Forced labor takes root in contexts that do not promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all. Decent work includes opportunities for work that are productive and deliver a fair income, security in the workplace, and social protection.

Metric | SDG target | Description |

|---|---|---|

Unemployment and underemployment [9] | 8.5 By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value | The level of unemployment and labor underutilization within countries. Unemployed or precariously employed people have increased levels of vulnerability to forced labor because they often have debt. With increased household debt due to unemployment and limited employment choices, workers take greater risks and accept work in exploitative conditions. In addition, as parents’ access to work decreases, the risk of child labor increases. |

Labor rights protections [4] | 8.8 Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment | The level of labor rights protections within countries. Forced labor risk is higher in contexts with poor labor rights protections, including collective bargaining, the minimum wage, limitations on working hours, protection from unsafe and unhealthy working conditions, and protection of children and young people. |

Youth unemployment [10] | 8.6 By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education, or training | The level of youth unemployment within countries. Traffickers often target unemployed youth. In contexts where job creation does not match population growth, young people attempt economic migration, making them vulnerable to exploitative recruitment practices. They risk incurring debt from migration costs and becoming trapped in forced labor to repay this debt. |

Resource efficiency and environmental protection [11] | 8.4 Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavor to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-year framework of programs on sustainable consumption and production, with developed countries taking the lead | The level of resource efficiency and environmental protection within countries. There are extensive links between environmental degradation and forced labor. Where a country's resource demand exceeds nature’s capacity to meet that demand, communities can be displaced, or their livelihoods in farming, fishing, or mining can be disrupted, leaving them in poverty and vulnerable to exploitation. |

Informal economic activity [12] | 8.3 Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity, and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services | The level of informal economic activity within countries. Workers in highly informalized sectors are more vulnerable to exploitation because they are often poor, socially vulnerable, and financially or economically dependent. Informal work is often more labor-intensive, and informal incomes are lower than equivalent work in the formal sector. |

Youth employment policies and action [4] | 8.b By 2020, develop and operationalize a global strategy for youth employment and implement the Global Jobs Pact of the International Labour Organization | The extent of youth employment policies and action within countries. Forced labor risks for young people are higher in contexts with low public expenditure on social protection and employment programs and are reduced through programs and strategies that promote education, fair recruitment, safe migration, and decent work. |

Financial inclusion [13] | 8.10 Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance, and financial services for all | The level of financial inclusion within countries. People who are unbanked and with limited access to affordable credit, insurance, or social protection schemes may seek to cover expenses by taking out loans from informal money lenders at high interest rates, attempting risky migration for work, or taking loans from employers. These behaviors can facilitate situations of forced labor, which can then lead to exploitative situations. Some may also receive advance payments or loans from employers, which can facilitate a bonded labor relationship. |

Economic growth [14] | 8.1 Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 percent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries | The level of economic growth within countries. Forced labor prevalence is significantly lower in countries with high levels of economic development. Contexts with low economic growth have greater vulnerability to forced labor as they have fewer job opportunities and less investment in education and healthcare. In turn, forced labor holds back overall economic growth and development by lowering productivity. |

Trade openness [15] | 8.a Increase Aid for Trade support for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, including through the Enhanced Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance to Least Developed Countries | The level of trade openness within countries. Countries with high levels of trade openness have lower levels of forced labor risk. Engaging in international trade can reduce the use of forced labor through its impact on income or through changes in regulations. Trade can trigger anti-forced labor policies in the country as trade partners demand higher labor standards. |

Economic contribution from tourism [16] | 8.9 By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products | The level of economic contribution from tourism within countries. Policies that promote sustainable tourism create jobs, improve infrastructure, and contribute to sustainable economic growth, helping to create a context of poverty reduction and decent work. |

SDG 1 - Poverty reduction - End poverty in all its forms everywhere

This category of metrics measures the extent of poverty. Rises in poverty lead to rises in forced labor. Income poverty but also other dimensions of poverty – access to credit, capital, education, and outside employment options - all increase vulnerability to exploitation. Poor and vulnerable workers must prioritize survival, accepting insecure or exploitive work, entering forms of debt bondage, and attempting risky migration that can become trafficking.

Metric | SDG target | Description |

|---|---|---|

Equal rights and access to economic resources [17] | 1.4 By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology, and financial services, including microfinance | The extent of equal rights and access to economic resources within countries. Modern slavery risks, including forced labor, are higher in contexts where women do not have equal rights and access to services, land, property, gainful employment without the need to obtain a male relative's consent, and non-discrimination from employers. Lack of protection for women's economic rights and lack of gender equality across reproductive health, empowerment, and the labor market leads to greater vulnerability for women to exploitation. |

1.2 By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions | The level of multidimensional poverty within countries. Nighttime light data, in combination with population data, enables monitoring of patterns in economic development and wealth, investments in infrastructure, and multiple dimensions of poverty risk. Contexts with deprivation across not just monetary poverty but also basic infrastructure services will have higher levels of inequality, extreme poverty, and vulnerability to exploitation. | |

Social protection coverage [20] | 1.3 Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable | The extent of social protection coverage within countries. Contexts with poor social protection benefits have higher risks for forced labor. Without extending protection through contributory social insurance, tax-funded social assistance, and other schemes providing basic income security, countries cannot reduce poverty, inequality, and vulnerability to exploitation. |

1.1 By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than US$1.25 a day | The level of extreme poverty and income inequality within countries. Forced labor takes root and persists in contexts with high levels of extreme poverty. Difference in income, especially the income of the poorest in the population, is a significant driving factor encouraging individuals to undertake risky migration and accept work under exploitative conditions. | |

Quality of governance and public services [23] | 1.b Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional, and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions | The quality of governance and public services within countries. Countries with poor public services and policy implementation cannot effectively eradicate poverty and protect vulnerable workers from risks of exploitation. |

Government investment in essential services [4] | 1.a Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programs and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions | The level of government investment in essential services within countries. Forced labor can persist in contexts without adequate programs and policies to reduce poverty through services like education. |

Impact of economic shocks on vulnerable communities, including refugees [24] [25] | 1.5 By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social, and environmental shocks and disasters | The risk of economic shocks for vulnerable communities within countries. Forced labor risk increases during climate-related extreme events and other economic, social, and environmental shocks and disasters. Where a country has a poor overall quality of infrastructure and/or a large existing refugee population, these shocks create much higher levels of vulnerability to exploitation. |

SDG 13 - Climate action - Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

This category of metrics measures the extent of climate change-related impacts. Climate change, environmental degradation, and forced labor are highly interconnected. Climate change increases vulnerability to forced labor, and victims of forced labor are often forced into activities that destroy the environment. There is a positive relationship between stronger environmental protections and lower estimated levels of forced labor.

Metric | SDG target | Description |

|---|---|---|

Resilience to climate-related hazards and disasters [26] | 13.1 Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries | The level of resilience to climate change-related hazards and disasters within countries. In contexts with high levels of tree loss, the incidental biodiversity loss contributes to pervasive poverty, loss of livelihoods, and food insecurity, exposing vulnerable populations to higher risks of forced labor. In turn, their forced labor in illegal deforestation leads to further tree loss. |

Climate change-related hazard exposure [27] | 13.3 Improve education, awareness-raising, and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction, and early warning | The level of climate change-related hazards and disasters within countries. Earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, tropical cyclones, and droughts exacerbate vulnerabilities conducive to forced labor, including economic inequalities, displacement, and lack of access to essential services. Unstable environments in the wake of a natural disaster may incentivize predatory behavior and risky survival strategies, increasing exploitation risk. |

13.2 Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning | The extent of measures to reduce carbon emissions within countries. Enslaved people are forced to work in ways that are extremely destructive. The emissions from forced labor are larger than the national emissions from Canada, Germany, and the UK combined. Sustained success in developing national policies and strategies that reduce carbon emissions will also mean measures to regulate industries that are environmentally destructive and have high levels of forced labor. | |

Climate change adaptation and mitigation planning [27] | 13.b Promote mechanisms for raising capacity for effective climate change-related planning and management in least developed countries and small island developing states, including focusing on women, youth, and local and marginalized communities | The extent of climate change adaptation and mitigation planning within countries. Vulnerability to forced labor due to climate change-related hazards is increased when a country has not taken actions to increase its society's resilience to cope with disasters, including for vulnerable communities. |

Climate change adaptation and mitigation infrastructure [27] | 13.a Implement the commitment undertaken by developed-country parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation and fully operationalize the Green Climate Fund through its capitalization as soon as possible | The extent of climate change adaptation and mitigation infrastructure within countries. Vulnerability to forced labor due to climate change-related hazards is increased when a country does not have strong existing infrastructure to provide emergency response and recovery, such as communication networks and accessible health systems. |

Overall risk categorization technique

Risk categories aid the assessment of risk and simplify the prioritization of response. They are overlaid onto scores, which are the primary guidance for risk. Organizations with different risk appetites may have different points at which they trigger action/controls.

The establishment of risk categories is an inherently subjective process. One common approach is to consider how scores are distributed across multiple organizations and multiple sub-scores for an individual organization. Such an approach gives an indication of relative risk, enabling the decision-maker to make judgments - between organizations, or between competing factors for a given organization. With this risk solution, the consideration of such a distribution to inform the choice of categories is complicated by the generation of scores at many levels: metrics, groupings of metrics (for example, sustainable development goals or suppliers and subsidiaries), business/country/industry levels, and an overall score. Here a high-level assessment of scores at many levels, and for a number of organizations, was combined with an analysis of the distributions of the most detailed individual metric scores across all countries and all industry categories, to inform the thresholds that delineate each risk category. The intention was to distribute risk scores relatively evenly across categories. Nevertheless, acknowledging the variation in risk appetite across organizations when making informed decisions, specifically the interpretation of and response to risk scores generated here, the user is free to redefine the risk thresholds to match their requirements.

Product flag component

Independent of the solution’s risk scoring system, the solution contains a product risk dataset. Through a wide-ranging assessment of existing, up-to-date repositories of information on products that have been explicitly linked to instances of forced labor - and the specific countries where the violations occurred – the Rights Lab constructed an extensive record of product-country forced labor cases [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65]. In this way, ‘flags’ can be raised against problem products that may be of specific interest to an organization.

To compile this data into a usable resource, products are mapped onto Harmonized System (HS) Codes. HS codes are a widely recognized standard classifier of traded products that enable alignment of each product in the product-country slavery record with recognized numerical identifiers. The recording of instances of forced labor violations ranges from quite explicit about the exact product, to somewhat general categories. To accommodate this spectrum of product descriptions, a mapping of the record to the appropriate HS coding level has been completed, as the identifier can vary in specificity according to the number of digits used in the code. Nominally 6-digit HS codes are employed, which align with quite detailed product descriptions. However, in some instances, more general 4-digit or even 2-digit codes are employed where appropriate.

In the product risk tool, given an identifier – even only a high-level identifier at the 2-digit or 4-digit level - the user can check if a flag has been raised against a product and identify the specific countries of concern.

Recommendations database

Beyond the generation of forced labor risk scores for an organization, there is a need for practical information on how an organization might respond to key risks. The Rights Lab’s database of recommendations links to the scores and specific metrics. Through extensive literature review, interviews with experts, and expert evaluation of best practice approaches, the Rights Lab constructed a database of recommendations for effective response. These recommendations align with global practice, specifically the UN Global Compact initiative, UN Guiding Principles, International Labour Organization (ILO) guidance, expectations for Modern Slavery Act reporting, and KnowTheChain benchmarking methodology.

Individual recommendations have been generated for each of the 10 business metrics, 33 country metrics, and 26 industry metrics. For the three questionnaire-based business metrics, recommendations are at the individual question level. Recommendations can be accessed at the metric level and will be highlighted for the worst-performing metrics (i.e., the areas of highest risk).

Appendix - Definitions

Modern slavery

Modern slavery is not defined in international law but is used as an umbrella term by governments and the UN to cover practices such as forced labor, debt bondage, forced marriage, and human trafficking. The term refers to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because of threats, violence, coercion, deception, and/or abuse of power. Where the terms slavery or contemporary forms of slavery are used, this is defined in international law as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised” (UN Slavery Convention, 1926). Today, the exercise of “the powers attaching to the right of ownership” can be understood as constituting control over a person in such a way as to significantly deprive that person of his or her individual liberty, with the intent of exploitation through the use, management, profit, transfer, or disposal of that person. Usually, this exercise will be supported by and obtained through means such as violent force, deception, and/or coercion. Our solution includes data and metrics that measure the risk of modern slavery across all the practices that are relevant to supply chains and business operations.

Forced labor

Forced labor is defined in international law as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily” (ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930, No. 29). Our solution includes data and metrics that measure risk in line with the ILO’s 11 indicators of forced labor—the most common signs or “clues” that point to the possible existence of a forced labor case.

Human trafficking

Human trafficking (or trafficking in persons) is defined in international law as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” (UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, 2000). Our solution includes data and metrics that measure the risk of human trafficking, including countries’ provisions in laws, policies, and action plans to effectively combat the problem.

Citations

[1] Corruption Perceptions Index 2021 by Transparency International, licensed under CC-BY 4.0. Dataset changed by subtracting scores from 100.

[2] Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. The Global Organized Crime Index 2021.Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. The Global Organized Crime Index 2021.

[3] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download/?url=kiKX83.

[4] UNdata.

[5] UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, Version 21.1. Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Håvard Strand (2002) Armed Conflict 1946-2001: A New Dataset. Journal of Peace Research 39(5).

[6] Gibney, Mark, Peter Haschke, Daniel Arnon, Attilio Pisanò, Gray Barrett, Baekkwan Park, and Jennifer Barnes. 2023. The Political Terror Scale 1976-2022. The Political Terror Scale website: https://www.politicalterrorscale.org.

[7] U.S. State Department: Trafficking in Persons Report 2021.

[8] Ferrant, G., L. Fuiret and E. Zambrano (2020), "The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019: A revised framework for better advocacy", OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 342, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/022d5e7b-en.

[9] Labour Force Statistics (LFS) Database. The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the original source.

[10] The World Bank: Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15-24) (modeled ILO estimate). Data source: International Labour Organization. “ILO Modelled Estimates and Projections database (ILOEST)” ILOSTAT.

[11] 2023 EDITION NATIONAL FOOTPRINT AND BIOCAPACITY ACCOUNTS (DATA YEAR 2019): https://www.footprintnetwork.org/licenses/public-data-package-free/; sum of "Total Ecological Footprint (Production)" and "Total Ecological Footprint (Consumption)". License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation.

[12] The World Bank: Multiple indicators multiple causes model-based (MIMIC) estimates of informal output (% of official GDP). Data source: Elgin, C., M. A. Kose, F. Ohnsorge, and S. Yu. 2021. “Understanding Informality.” CERP Discussion Paper 16497, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

[13] The World Bank: Borrowed from a financial institution or used a credit card (% age 15+). Data source: Global Findex database.

[14] The World Bank: GDP per capita growth (annual %). Data source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

[15] The World Bank: Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) and Imports of goods and services (% of GDP). Data source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

[16] © World Travel & Tourism Council: Indicator 24693, Travel and Tourism total contribution to GDP (Percentage share of total GDP), 2021. All rights reserved.© World Travel & Tourism Council: Indicator 24693, Travel and Tourism total contribution to GDP (Percentage share of total GDP), 2021. All rights reserved.

[17] United Nations Development Programme: Gender Inequality Index (Value). License: https://hdr.undp.org/terms-use. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation.

[18] Earth Observation Group, Payne Institute for Public Policy: C. D. Elvidge, K. Baugh, M. Zhizhin, F. C. Hsu, and T. Ghosh, “VIIRS night-time lights,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 38, pp. 5860–5879, 2017.

[19] Oak Ridge National Laboratory.Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

[20] Social protection effective coverage: SDG 1.3.1 – Population covered by at least one social protection benefit (excluding health). The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the original source.

[21] The World Bank: GDP per capita, PPP (current international $). Source: International Comparison Program, World Bank | World Development Indicators database, World Bank | Eurostat-OECD PPP Programme.

[22] United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Index (HDI). License: https://hdr.undp.org/terms-use. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation.

[23] The World Bank: Government Effectiveness. Data source: Estimate: Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi (2010). "The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430 (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1682130).

[24] WEF Global Competitiveness Index - Historical Dataset: Quality of overall infrastructure, 1-7 (best). World Economic Forum. Original link to the report: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2016-2017/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2016-2017_FINAL.pdf.

[25] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download/?url=8SD27y.

[26] Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. "High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change." Science 342 (15 November): 850-53. Data available online at: https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-change.

[27] INFORM Risk 2024, European Commission. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation.

[28] “Data Page: Annual CO₂ emissions”, part of the following publication: Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado and Max Roser (2023) - “CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Data adapted from Global Carbon Project. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/annual-co2-emissions-per-country [online resource].

[29] The World Bank: Population, total (SP.POP.TOTL). Data source: (1) United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2022 Revision. (2) Census reports and other statistical publications from national statistical offices, (3) Eurostat: Demographic Statistics, (4) United Nations Statistical Division. Population and Vital Statistics Report (various years), (5) U.S. Census Bureau: International Database, and (6) Secretariat of the Pacific Community: Statistics and Demography Programme. Note dataset combined with another dataset and transformed through normalization.

[30] World - KNOMAD-ILO Migration Costs Surveys 201. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) & International Labour Organization (ILO), The World Bank.

[31] Not used.

[32] ILO and the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs of Viet Nam, Viet Nam National Child Labour Survey 2018: Key findings, Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2020.

[33] FUNDAMENTALS, Timor-Leste National Child Labour Survey 2016 - Analytical Report, Geneva: International Labour Office, 2019.

[34] FUNDAMENTALS and Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia. Ethiopia National Child Labour Survey 2015 / International Labour Office, Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS); Central Statistical Agency (CSA). – Addis Ababa: ILO, 2018. The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the original source.

[35] National Child Labour Survey 2016 of Jordan. Center for Strategic Studies University of Jordan In Collaboration with International Labour Organisation(ILO) & Ministry of Labour & Department of Statistics. Amman, August 2016.

[36] ILO and Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. Tanzania National Child Labour Survey 2014: Analytical Report / International Labour Office; Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (FUNDAMENTALS); Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. - Geneva: ILO, 2016. The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the original source.

[37] Source: INEGI, NOTA TÉCNICA RESULTADOS DE LA ENCUESTA NACIONAL DE TRABAJO INFANTIL (ENTI) 2019.

[38] Source: INEGI, Encuesta Nacional de Trabajo Infantil (ENTI) 2019; 7 de diciembre, 2020.

[39] The International Labour Organization (ILO) and Understanding Children's Work (UCW). Measuring children’s work in South Asia - Perspectives from national household surveys by Sherin Khan and Scott Lyon, 2015.

[40] United Nations Global Compact.United Nations Global Compact.

[41] The International Labour Organization (ILO). Copyright © International Labour Organization. ILO publications are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution BY 4.0 licence (CC BY 4.0). This is an adaptation of a copyrighted work of the International Labour Organization (ILO). This adaptation has not been prepared, reviewed, or endorsed by the ILO and should not be considered an official ILO adaptation. The ILO disclaims all responsibility for its content and accuracy. Responsibility rests solely with the author or authors of the adaptation. Source: https://rshiny.ilo.org/dataexplorer9/. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

[42] European Energy Agency (EEA): Data source: https://sdi.eea.europa.eu/data/3da7d329-beea-4a7b-89bc-d45fc1c4b8ac?path=%2FEXCEL. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation. Copyright notice: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/legal-notice. License notice: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Disclaimer - the EEA accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever (including but not limited to any direct or consequential loss or damage that might occur to you and/or any third party) arising out of or in connection with the information on this site. The information the EEA provides on this site does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the EEA and other European Union institutions and bodies.

[43] Hannah Ritchie (2020) - “Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector' [Online Resource]; License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ with original data sourced from Climate Watch (2023) – with major processing by Our World in Data. Note dataset further changed through normalization transformation.

[44] Mekonnen, M.M. and Hoekstra, A.Y. (2011) National water footprint accounts: the green, blue and grey water footprint of production and consumption, Value of Water Research Report Series No. 50, UNESCO-IHE, Delft, the Netherlands.

[45] The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU LFS).

[46] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Skills for Jobs Indicators, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264277878-en.

[47] Martins Guilhoto, J., C. Webb and N. Yamano (2022), “Guide to OECD TiVA Indicators, 2021 edition”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2022/02, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/58aa22b1-en.

[48] Galindo-Rueda, F. and F. Verger (2016), "OECD Taxonomy of Economic Activities Based on R&D Intensity", OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2016/04, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlv73sqqp8r-en.

[49] OECD (2023), National Accounts of OECD Countries, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3e073951-en.

[50] World Bank Enterprise Surveys, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org.

[51] The European Commission. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Note data used was changed through normalization transformation.

[52] The International Labour Organization (ILO). License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Note data used was changed through normalization transformation.

[53] World Bank. 2020. 2020 State of the Artisanal and SmallScale Mining Sector. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Note data used was changed through normalization transformation.

[54] O’Driscoll, D. (2017). Overview of child labour in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector in Asia and Africa. K4D Helpdesk Report. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. License: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/.

[55] The International Labour Organization (ILO).

[56] U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

[57] Brown C, Daniels A, Boyd DS, Sowter A, Foody G, Kara S. Investigating the Potential of Radar Interferometry for Monitoring Rural Artisanal Cobalt Mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239834. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Note dataset changed through normalization transformation.

[58] https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/products_of_slavery_and_child_labour_2016.pdf. Sources of information: www.dol.gov, www.danwatch.dk, www.theguardian.com, www.hrw.org. Note: these are sources collated in 2016 which is within the timespan of the SDG goals set in 2015 and the basis of the risk assessment model. Further data may now be available and will be added at the next data refresh.

[59] U.S. Department of Labor.

[60] Strengthening Protections Against Trafficking in Persons in Federal and Corporate Supply Chains: Research on Risk in 43 Commodities Worldwide (Verité, 2017).Strengthening Protections Against Trafficking in Persons in Federal and Corporate Supply Chains: Research on Risk in 43 Commodities Worldwide (Verité, 2017).

[61] U.S. Department of Agriculture.

[62] U.S. International Trade Commission.

[63] Ripe With Change: Evolving Farm Labor Markets in the United States, Mexico and Central America, Philip Martin and J.Edward Taylor (Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC, 2013) https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/RMSG-Agriculture.pdf.

[64] U.S. State Department.

[65] Brown C, Boyd DS, Kara S. Landscape Analysis of Cobalt Mining Activities from 2009 to 2021 Using Very High-Resolution Satellite Data (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9545. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159545.